By Sara Shipley Hiles

Globe Correspondent

Is it possible that secondhand smoke causes breast cancer?

By Sara Shipley Hiles

Globe Correspondent

Is it possible that secondhand smoke causes breast cancer?

This article was originally published in The Nation, July 9, 2007

By Sara Shipley Hiles

It’s a long way from the thin air of an impoverished mountain village outside Lima, Peru, to the tony atmosphere of the Hamptons. But a group of religious leaders from Peru recently traveled to New York to tell billionaire industrialist Ira L. Rennert that even if he can sleep at night, comfortably ensconced in his 110,000-square-foot estate in Sagaponack, God is watching.

The clerics want Rennert to improve health care and dramatically decrease emissions at a metals smelter in La Oroya, Peru, a town high in the Andes Mountains where thousands of children are suffering from lead poisoning. The smelter, known as Doe Run Peru, is a subsidiary of Rennert’s $2.4 billion private holding company, the Renco Group.

Peruvian Roman Catholic Archbishop Pedro Barreto publicly called upon Rennert, a well-known philanthropist and supporter of Orthodox Jewish causes, to honor his religious faith and work harder to solve La Oroya’s pollution problems.

“Our main purpose was to invite Ira Rennert to become a leader in social responsibility, under the assumption this is an ethical and moral issue,” Barreto said, during the group’s three-city visit to the United States this month.

Rennert declined to meet with Barreto and his colleagues, referring them to a local representative for the smelter in Lima. The religious delegation–which included an evangelical pastor, a Jewish leader and several Catholic nuns–instead visited with various religious agencies during the stop in New York City.

Calls to Rennert’s office at Rockefeller Center asking for comment on the visit were referred to Victor Belaunde, a Doe Run Peru spokesman in Lima. Belaunde said that company officials met with the religious leaders June 8 in Lima and updated them on ongoing environmental improvements.

Company officials claim Doe Run Peru has already committed more than $107 million to clean up the smelter in the decade since Renco acquired the facility. The company pays $1 million annually to fund a health program run by the government’s health ministry, Belaunde said. He added that the smelter is now in compliance with Peruvian standards for lead emissions.

Despite these investments, a recent study by St. Louis University scientists found that 97 percent of children in La Oroya are lead-poisoned, a condition that can cause mental and physical deficiencies. And a new report from LABOR, a Peruvian non-profit group, found that emissions of lead, arsenic and sulfuric acid have actually increased in the past two years, according to Friends of La Oroya, a group supporting the religious leaders’ delegation.

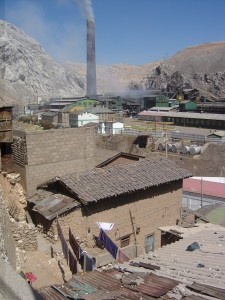

The city of 33,000 people has been declared one of the world’s ten most polluted places by the Blacksmith Institute. Visitors to La Oroya first notice that the surrounding valley looks like a bomb crater, stripped bare of vegetation by acid rain. Then they notice the massive Doe Run smelter complex, which bathes city in choking fumes and toxic dust that contains cadmium, arsenic and lead.

To combat the dust, Doe Run organizes cadres of women to wash public streets and encourage children to wash their hands. The company has delayed some mandatory environmental work that was originally required to be completed in 2006. Now the work is set to be done by 2009, but even then, according to the company’s own study, many children in the town will still have blood-lead levels well above the acceptable standard.

“In the last few years the pollution in the air is worse, the soil has become infertile and the water has become polluted,” said Sister Mila Diez, a Dominican nun from La Oroya who was part of the religious delegation. “We don’t want to fight with the company. We don’t want the company to close their doors. What we want is for them to comply with the promise they made to clean the air.”

The religious leaders’ tour also stopped in St. Louis, where Doe Run Peru’s former parent company, Doe Run Resources, has its headquarters. Company officials there declined to meet with the group, saying that Doe Run Peru is no longer its subsidiary; the Peruvian company now reports directly to Renco.

In addition, the group visited Herculaneum, Mo., where Doe Run operates the largest lead smelter of its kind in the United States. Longtime environmental activist Tom Kruzen took the group on a “toxic tour” to see the neighborhood where Doe Run was forced to buy out more than 140 homes surrounding the plant.

“You can pray all you want,” Kruzen said of Rennert, “but if you’re doing bad things to people, or if your endeavors do bad things to people, then you’re not a moral person.”

Rennert has grown rich using a formula of buying dirty companies, taking out steep loans and paying himself princely dividends, as documented in articles in Forbes and Business Week. Several of his companies have filed for bankruptcy, allowing Rennert to buy back assets for pennies on the dollar. Rennert’s empire of mining and manufacturing firms also includes AM General LLC , the maker of HUMVEE military vehicles and the gas-guzzling Hummer, as well as a magnesium producer and a steel manufacturer.

The wealthy financier also has given widely to charitable and civic causes. Rennert and his wife, Ingeborg, have contributed to restoring the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem, where the visitor’s center bears the name “The Ingeborg and Ira Leon Rennert Hall of Light.” New York University has an endowed professor of entrepreneurial finance in Rennert’s name, and the Rennerts donated between $1 and $1.9 million to the World Trade Center Memorial .

At one time, Rennert lent his name to the Torah Ethics Project, an effort to remind Orthodox Jews of the importance of “living in accordance with the highest ethical standards.” A statement on the project’s website urges moral behavior in all business and personal matters that “adds luster to God’s sacred name.”

Rennert’s supporters have included Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Holocaust survivor. At the prestigious Fifth Avenue Synagogue in New York, where Rennert is chairman, Rabbi Yaakov Kermaier defended Rennert’s reputation.

“I’m not really familiar with any of his business operations,” Kermaier said in an interview. “I know him as a person of extraordinary generosity and unimpeachable personal integrity.”

In a cloud forest in Panama, hundreds of frogs turn up dead, the life sucked out of them by a strange fungus.

In the wetlands of northwest Iowa, where hunters once collected 20 million frogs a year for their meaty legs, there is only one leopard frog left for every thousand frogs the pioneers saw.

In southern Missouri’s mountain streams, scientists struggle to protect dwindling populations of the Ozark hellbender, a wrinkled, primitive salamander that can grow to two feet long.

All around the planet, amphibians such as these are in trouble. It’s not just the colorful, exotic rainforest species that are disappearing, but also the common frogs, toads, newts and salamanders that people used to see in backyards across America.

A third of all amphibian species are considered threatened, making them the most vulnerable group of animals in the world. By comparison, 12 percent of birds and 23 percent of mammals are threatened.

Amphibians—named for the Greek word for “double life”—are moist-skinned vertebrates that have distinct larval and adult stages. Typically spending part of their lives on land and part in water, these change artists have thrived on Earth for 360 million years. But without swift action, many scientists and conservationists believe that much of their diversity will soon vanish. An estimated 120 of approximately 6,000 known amphibian species have disappeared in the past 25 years, and another 2,000 to 3,000 species may go extinct in our lifetimes.

“It sounds like hyperbole, but really, this is the greatest conservation challenge humanity has ever faced,” says Kevin Zippel, program officer for Amphibian Ark, a $50-million effort to collect critically endangered species from the wild for protection and breeding in zoos and aquariums. “The world hasn’t seen an extinction crisis like this since the dinosaurs died out.”

The Amphibian Ark is part of a larger program, the Amphibian Conservation Action Plan, created by staff from conservation groups, universities, zoos, government agencies and others around the world. This is a broad plan to counter threats to amphibians, which range from habitat loss, disease and overharvesting to global warming, pollution and UV radiation. The estimated cost of this effort is $400 million over a five-year period.

To help raise awareness and funding for amphibians, organizers have dubbed 2008 the “Year of the Frog.” The campaign kicked off on New Year’s Eve with a series of “leap year” events focused on the plight of amphibians. Other activities planned for the year include a worldwide petition drive and special events at zoos, aquariums and museums. The tone of these celebrations is light, but the crisis behind it often has herpetologists speaking in somber tones.

“These are tragic circumstances we find ourselves in,” says George Rabb, retired president of the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago and a member of Defenders of Wildlife’s board. “We either do something to give amphibians some security, or it’s likely that many of these creatures will absolutely vanish from this Earth.”

The most urgent problem, scientists say, is a fungus that can kill up to 80 percent of native amphibians within months of its arrival in an area. Formally known as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd for short, the deadly agent is commonly referred to as a chytrid fungus.

Biologist Karen Lips helped track the fungus’ wavelike spread through Central America. In 1992, she encountered a handful of dead frogs in Costa Rica, but she didn’t think much of it. Four years later, when she found 50 dead frogs at a site in Panama, she knew something was wrong. The frogs looked fine, but they didn’t move, as if they had been frozen in place. “It’s like they went to sleep sitting on their little rock or leaf, and they just died right there,” says Lips, who works at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale.

The frogs died of a chytrid infection, but no one knew that at the time. The fungal disease wasn’t identified until 1997, when scientists from around the world gathered to look at the organism under an electron microscope and agreed that it was the same pathogen decimating frogs from Australia to the United Kingdom. Since then, the fungus has been discovered in most of the world, with a few exceptions, such as Madagascar, New Guinea and parts of Asia, Rabb says.

The origin of the fungus is still a mystery. The prevailing hypothesis holds that it originated in Africa and spread around the globe through the export of the African clawed frog, a common lab animal once used in human pregnancy testing. More recently, trade in the American bullfrog and other species used for food and pets may have spread the fungus, but no one is quite sure how it gets around. It is unstoppable and untreatable in the wild. “We can’t really track it in nature yet,” Lips says. “We just stake it out and wait for it to get there.”

Some amphibians appear to be immune to the disease, but others are completely wiped out. Joe Mendelson, curator of herpetology at Zoo Atlanta, compares the spread of chytrid to the smallpox epidemic that swept through Native American populations after European settlers arrived, leaving few survivors. “That’s what we have with amphibians right now—groups that have survived,” he says. “In southern Mexico, at one of my study sites, there are still amphibians there, but you’re looking at what was left after everything else was killed.”

After witnessing six or seven population crashes and finding hundreds of dead frogs in Central America, Lips is shifting some of her work to the United States. She plans to embark on a survey of frogs across Illinois to see how widespread the pathogen is there. “Honestly, we’re limited in what we can do down there (in Central America), because we’re running out of frogs,” she says.

Such sobering realizations have led to amphibian rescue missions like one Mendelson helped lead at a site known as El Valle in Panama in 2005. With the blessing of the Panamanian government, a team of Americans and Panamanians conducted what Mendelson calls a “pre-emptive conservation strike,” capturing about 600 frogs from 35 species and taking them back to facilities in Atlanta. At the same time, the Houston Zoo was building an amphibian conservation center in Panama. Within a year of the extraction, the fungus showed up at El Valle and wreaked its havoc, and “now the place is almost completely frogless,” Mendelson says.

The Amphibian Ark program promotes more of these rescue operations for about 500 species deemed to be in imminent danger. Zippel says the Ark will target many species in tropical forests, where the fungus is hitting particularly hard, but it will also include American species such as the California mountain yellow-legged frog and the Mississippi gopher frog. Each species will be housed in two biologically secure facilities to guard against unexpected loss. For remote areas, commercial shipping containers can be converted into self-contained labs run on solar power. “Literally, wherever amphibians are in need, we can put one” of the labs, Zippel says.

The idea is to keep a sliver of the population alive so that the animals can be released to the wild when—or if—it’s safe. “We could have the fungus cured tomorrow, or never,” Zippel says. “It’s really a stopgap measure, to buy us some time.”

Even if chytrid fungus could be tamed, amphibians face a host of other problems. Habitat loss is still chief among them, according to a 2004 global survey. Mike Lannoo, editor of a comprehensive book about amphibian declines in the United States, blames habitat loss for the one amphibian extinction documented in the United States to date. “The Vegas Valley leopard frog was last seen in 1942. Basically, Bugsy Siegel built Las Vegas over its habitat,” Lannoo says.

Of the 291 species remaining in the United States, Lannoo estimates that two-thirds are in decline. About 10 percent are at severe risk. Only a few are increasing in numbers, often because of their introduction into non-native habitats, he said. Even those species that are still common are less so than they once were, he says.

For example, leopard frogs swarmed the shores of Lake Okoboji in northwestern Iowa so heavily a century ago that hunters were able to collect 20 million of the spotted greenish-brown frogs a year. “If you go to that same spot now, which I have, what you find is a three orders of magnitude decrease. You might say there are still plenty of frogs, and that’s true, but there are 1,000 times fewer frogs,” Lannoo says. Swamp draining in the early 20th century killed the commercial frog industry, and later, amphibians suffered from the application of pesticides and the introduction of carnivorous sport fish such as muskies, he says.

The tiger salamander, the most widespread salamander species in the United States, is another example of a once-common species that has declined. Growing up to a foot long, the tiger salamander is secretive, spending most of its time burrowed underground. While still thriving in some areas, tiger salamanders have been eliminated in much of their former range, and a number of studies have documented sharp drops in local populations.

“The biggest factor in amphibian decline is habitat loss and habitat alteration,” Lannoo says. “But as a society, the things we’re doing almost universally negatively impact amphibians: global warming, ozone depletion, acid rain, applying pesticides, planting non-native species, moving fish around, spreading disease.”

Adding these factors together may create the perfect storm that’s killing amphibians. Threats to the Ozark hellbender salamander, for example, include habitat loss, overcollection and pollution from man-made chemicals, such as endocrine disruptors. Recently, researchers found some hellbenders infected with chytrid fungus as well.

Tyrone Hayes, the University of California-Berkeley researcher who has studied the impacts of the weed-killing chemical atrazine on frogs, says that environmental chemicals play a significant role in amphibian decline. Hayes led a recently published study that found immune system damage in frogs exposed to a cocktail of nine pesticides commonly used on corn fields. “I would never say atrazine and other pesticides are causing the global amphibian decline, but I do think they’re involved by making them more susceptible to diseases that would otherwise not impact them,” he says. (Syngenta, a major manufacturer of atrazine, says its studies have not found the herbicide to be harmful to amphibians. “We saw no effect on sexual development, and no effect on the general health of the animal either,” says Tim Pastoor, principal science advisor for Syngenta. Although atrazine is banned in some European countries, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency re-approved its use in 2006.)

If amphibians disappear, what then? Lips’ work has shown a cascade of effects in the ecosystem. Amphibians sit in the middle of the food web, so when frogs go, it affects both the things they eat and the things that eat them. Tadpoles eat algae and sediment in streams, so if there are no tadpoles, algae grow unchecked and sediment increases, leading to changes in water quality and aquatic insects. Adult frogs eat insects, so if there are no hungry frogs, some insect populations boom. And some snakes depend on frogs for food, so without their prey, those snakes may starve to death.

Amphibians also carry secrets of biomedicine that could be lost forever. Researchers at Vanderbilt University in Nashville have discovered anti-microbial substances in the skin of certain frogs that stopped HIV infection. The Australian red-eyed tree frog had the highest levels of such virus-blocking substances. “Theoretically, there could be some kind of cream developed that could protect against HIV transmission,” says Louise Rollins-Smith, a microbiologist who participated in the study.

The other selfish reason for humans to take notice is that frogs and salamanders are telling us something, says Robin Moore, an amphibian specialist at Conservation International who is helping to coordinate the worldwide amphibian conservation plan. “Amphibians are sensitive to change, and may simply be the first to go. They are sounding an alarm, an early warning that the ecosystems in which they live are not healthy,” he says. “We do not know what will be next to go—birds, mammals—or us?”

Learn more about the conservation of amphibians.

Sara Shipley Hiles is a freelance writer specializing in environmental topics. She teaches journalism at Western Kentucky University.

By Sara Shipley Hiles and Marina Walker Guevara

Leslie Warden had been on a plane only once before traveling to Peru in April 2003. She didn’t speak Spanish, had no college education, let alone a toxicology degree. Yet here she was, testifying in Lima’s stately Legislative Palace, in a hearing room filled with legislators and their staffs, representatives from government health and mining agencies, television cameras, and reporters. She’d come to talk about the Doe Run Co., one of the world’s largest lead producers, which operated a smelter in her hometown of Herculaneum, Missouri. The company now faced scrutiny over its smelter in La Oroya, a town high in the Andes Mountains where virtually every child had lead poisoning. The Peruvian Congress was considering whether to declare it a disaster zone.

Warden’s voice wavered as she addressed the session, but her mere presence made the Doe Run executives in the room flip open their cell phones and begin dialing frantically. “I came here,” she said, “to share some of what Herculaneum has learned and experienced over the last few years…. Our children should not continue to be the price the world pays for lead.” In both Missouri and Peru, Warden and other witnesses testified, Doe Run had polluted communities while hiding behind a screen of denials and misinformation, leaving parents unaware of the risks that the dust covering their homes, yards, and streets posed to their children.

The story of these two towns and how they found each other illustrates an increasingly common pattern: A company faced with mounting public pressure and environmental costs in the United States expands its dirty operations abroad, where regulations are lax, labor costs low, and natural resources abundant – and where impoverished people become dependent on the jobs and charity of the very business that causes them harm.

Like many people in Herculaneum, a town of 2,800 along the Mississippi River 30 miles south of St. Louis, Leslie Warden and her husband, Jack, were unaware of exactly what came belching out of the 550-foot smokestack about a quarter mile from their house. High school sweethearts, they’d bought a fixer-upper in 1988. Jack worked as a union carpenter, Leslie as a bookkeeper and secretary. Many of their neighbors had jobs at the Doe Run smelter, which employs about 240 workers and produces up to 250,000 tons of lead a year. Sometimes fumes from the plant made it hard to see across the street. “My wife would wash clothes and hang them on the line, and she’d have to rewash them because they’d get soot on them from the smelter,” Jerry Martin, a former mayor, recalls. Occasionally, someone from the company would come around to test the tap water or offer free grass seed to fill in the bare spots in residents’ yards. When an acid plume drifted over from the plant and corroded the paint on cars, the company would pay for the bodywork.

In 1997, a plume damaged Leslie Warden’s brand-new Mustang, and this time Doe Run refused to fix it. If the plant’s emissions could harm her car, she wondered, what about her 13-year-old son’s lungs? Could his add be connected to pollution from the smelter? She started calling public health and environmental agencies, inquiring about the gray, sticky deposits on her deck, the trucks that rumbled through town, and the acrid air.

The history of lead is a long and deadly one. Today, we know that exposure to lead causes anemia, high blood pressure, developmental delays, behavioral problems, decreased intelligence, and central nervous system damage. Children are the most vulnerable; no amount of lead in their bloodstreams is considered safe. But the malleable silver-gray metal has always held an allure. Ancient Egyptians laced pottery glaze with lead, and some scholars believe that its use in piping water, sweetening wine, and seasoning food contributed to the fall of Rome.

The U.S. government began phasing out leaded gasoline in 1973, after research showed that lead exposure harms the nervous system. It banned the sale of residential lead-based paint in 1978. Yet because lead remains an important component in electronics, computer monitors, and car batteries–which typically contain 21 pounds of lead–worldwide consumption has grown to more than 6 million tons a year.

Even when the evidence of lead’s harmfulness became insurmountable, the industry insisted its products were safe if used properly, and it routinely suppressed data that proved their toxicity. Many companies, including Doe Run, have also made a practice of blaming the victims: children who put lead-painted toys in their mouths, or uneducated parents who live in decrepit houses. As David Rosner, a public health historian at Columbia University and an expert witness in a lawsuit against Doe Run, concludes, “It’s really a pattern that develops. Shirking responsibility, denying the reality of the research, saying it wasn’t their lead. So kids continue, to this day, to suffer.”

Herculaneum had been polluted for decades, but public sentiment toward Doe Run began to sour in the early ’90s, after an ugly labor dispute. The smelter’s emissions repeatedly violated air-pollution rules, and many children were tested with high levels of lead in their blood. Some residents joined a personal injury lawsuit against the company, in the beginning of what would become an avalanche of suits against it. After the Fish and Wildlife Service found high levels of lead in fish, mice, frogs, and birds near Herculaneum, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Missouri Department of Natural Resources issued an order in 2000 requiring Doe Run to install new pollution controls and clean up residents’ yards that had lead levels exceeding epa standards. If the smelter’s emissions didn’t come into compliance, the company would be forced to limit its production capacity by 20 percent.

It was the toughest enforcement action ever taken against Doe Run, but the Wardens remained skeptical. Their teenage son had passed the age when children are most vulnerable to lead poisoning, but their young niece and nephew had been diagnosed with high blood-lead levels. Leslie Warden continued to scour reports, attend public meetings, and consult with environmental groups.

Finally, on an August night in 2001, Jack Warden cornered Dave Mosby, a state environmental official. Warden insisted that Mosby sample the black dust piled thick along streets Doe Run’s trucks used to haul lead to the smelter. The Wardens had long suspected the dust would test “hot.”

“It was close to midnight,” Mosby recalls. “But even from the streetlight, I could tell he had a real issue, because you could see the metallic luster of the dust in the street.” When Mosby got the results back several days later, he was stunned to learn that the dust was 30 percent pure lead. “We knew we had an emergency situation,” he says. The state health department declared Herculaneum’s lead contamination “an imminent and substantial endangerment” and posted signs warning parents not to let their children play in the street.

In February 2002, state health officials released a study showing that 56 percent of the children living within a quarter mile of the smelter had high blood-lead levels. In a settlement with the state, Doe Run offered to buy 160 homes located within three-eighths of a mile of the smelter. The relocations cost the company more than $10 million, on top of the millions it spent on cleanup.

Since 1994, the St. Louis-based Doe Run has been part of the Renco Group, the private holding company of New York businessman Ira Rennert. Rennert has earned a dubious reputation over his nearly 20 years in the mining business. His magnesium production company in Utah filed for bankruptcy in 2001, shortly after federal officials accused it of illegally disposing of hazardous waste. Another Rennert company, a steel producer in Ohio, paid millions of dollars in environmental penalties even as Rennert paid himself more than $200 million in dividends.

“He has gotten rich off junk bonds issued by metals companies he acquired, paid fines to clean up when he’s had to, stopped interest payments on bonds and bought back assets at pennies on the dollar,” a 2002 Forbes magazine story said of Rennert, who owns a 100,000-square-foot home in the Hamptons. “He has done it all within the law–and within plain view of investors.”

In 1997, with the climate in Herculaneum growing increasingly tense, Renco acquired a smelter in Peru. By 2005 the new facility was generating almost four times as much revenue as the Missouri smelter–and spewing 31 times as much lead into the air.

Four hours from Lima, the town of La Oroya is a labyrinth of narrow streets and one-room adobe houses located in Peru’s central sierra. Years of acid rain have stained the surrounding limestone mountains black and burned them bare of vegetation. Some call the copper-colored Mantaro River that runs through the area the “dead river” because contamination has snuffed out its plant and animal life. Wrapped in fumes, Doe Run’s smelter sits on the riverbank opposite the town of 33,000, dusting it with lead, arsenic, and cadmium. Sulfur in the air burns eyes and throats. In La Oroya Antigua, the neighborhood closest to the smelter, residents constantly wipe toxic dust off their furniture and windows.

An American company, Cerro de Pasco Copper Corp., built the smelter in 1922, and residents soon got used to covering their noses and mouths with handkerchiefs. As early as the ’60s, lead poisoning was known to be a problem for smelter workers, though studies weren’t conducted among the general population for three more decades. The Peruvian government took over the plant in 1974 and ran it for the next 23 years.

Doe Run acquired the aging complex in 1997 for $125 million, plus another $120 million in upgrades. The facility could produce up to 152,000 tons of lead a year, plus 2.4 million pounds of silver and almost 6,000 pounds of gold. Peru had just passed its first national environmental laws, and as part of the purchase, Doe Run agreed to comply with a 10-year environmental cleanup plan. It made some improvements, such as building a disposal pit for highly toxic arsenic trioxide. According to the company, its workers’ blood-lead levels dropped 30 percent, and lead and arsenic emissions from the main smokestack decreased more than a quarter over the next eight years. Yet a 2003 environmental study and government inspection records show that after Doe Run took over, the concentrations of lead, sulfur dioxide, and arsenic in La Oroya’s air increased. The study suggested that the causes were a 30 percent increase in lead production and “fugitive” emissions from the plant, which specializes in processing profitable “dirty ore” loaded with contaminants.

“Doe Run had to spend millions of dollars in Herculaneum to clean up the mess they created,” says Anna Cederstav, an environmental scientist with the law firm Earthjustice who has cowritten a book about La Oroya. “If they can go abroad and make a quick buck in places where they are not highly regulated, and send those profits home to pay the bills in the United States, they will absolutely do so.”

Doe Run spokeswoman Barbara Shepard calls that analysis “misguided.” She argues that La Oroya is better off today than it was when the Peruvian government ran the plant: Doe Run has spent more than $100 million to address environmental issues in La Oroya, and it plans to spend $100 million more in the next few years. “We are making the tough decisions alongside our community partners that will ensure sustainable development, economic growth, and improved environmental conditions,” Shepard says.

Like Herculaneum, La Oroya is a company town. Doe Run employs about 4,000 workers there, and those who don’t work at the smelter drive taxis and wash laundry for those who do. The company operates a soup kitchen and public showers, and gives away Barbie dolls and toy robots at Christmas. The city’s schools and even the police station are painted Doe Run’s corporate colors, green and white, and kids wear Doe Run sweat shirts. The company says it has spent more than $6.5 million on social programs in La Oroya and the surrounding communities.

Such corporate paternalism has a long history in Peru, observes Miguel Morales, former president of Peru’s National Mining Association. “Mining companies become the state, the government, the mother, the father–everything,” he says. Indeed, La Oroya’s mayor is a vocal supporter of Doe Run, and opposing it brings risk: The head of the Peruvian Directorate of Mining lost her job in 2005 after openly criticizing the company.

With fewer regulatory obstacles than in the United States, running a dirty smelter abroad can be far more devastating than at home. One study found that as many as 1 in every 50 people in one section of La Oroya could expect to get cancer; the epa’s acceptable risk range is 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 1,000,000. Multiple studies, including ones by Doe Run, have found that children under seven in La Oroya Antigua have blood-lead levels about three times higher than the internationally accepted standard. A 2005 study found 44 percent of children under five in the neighborhood had mental or motor deficiencies, and nearly 10 percent of children under seven had enough lead in their blood to warrant medical treatment.

“These children have been seriously damaged as a result of lead contamination,” says Jorge Albinagorta, head of Peru’s Office of Environmental Health. “Some have difficulties walking; others don’t respond well to stimulation or their growth is stunted.”

In person, these statistics take heartbreaking form. When Cristian Balbin, a quiet two-year-old with soft brown hair and brown eyes, was tested at 19 months, his blood-lead level was seven times the international standard. Four months later, at an age when most children begin speaking in sentences, Cristian could only point at things and moan. “He’s a little lazy, that’s why he doesn’t talk,” said his mother, Silvia Castillo, taking a break from washing clothes. Cristian rested listlessly in her arms, staring. She said that despite constantly sweeping her dirt floor and washing her children’s hands, she felt guilty “because I allowed him to pick up dust from the street and eat it.”

In La Oroya, Doe Run’s carefully crafted message muddies responsibility. A company-organized platoon of volunteer “environmental delegates” cleans the streets, goes door to door dispensing hygiene tips, and organizes public hand-washing sessions for children, who get smiley-face stickers when they complete the task. “Come on, clean. Move your brooms as if you were salsa dancing!” shouted environmental delegate Elizabeth Canales one morning as a dozen women scrubbed the streets of La Oroya Antigua with water provided by Doe Run trucks. “These are women who understand that if they don’t do something for their children, they will always live in the dirt,” says Dr. Roberto Ramos, a Doe Run physician.

Word about the problems in La Oroya traveled back to Missouri through Hunter Farrell, an American missionary who happened upon the town in 2001 and was moved by the sight of two young boys coughing violently in the streets. Two years later, Farrell facilitated the first meeting between residents of both towns in the basement of a Presbyterian church near Herculaneum. Missourians nodded as Dora Santana, a nurse from La Oroya, spoke of the “unknown plague” that had long afflicted the town. Rising to speak next was Mark Pedersen, who grew up in Herculaneum and had recently lost his daughter after a lifetime of health problems. “You can look up and down the street and name each household and the diseases they have or died from,” he said. “Lo mismo,” Santana replied–“The same.”

Two months later, Leslie Warden flew to Peru to testify at the congressional hearing. On her way, she stopped in La Oroya to see for herself the orange river and the pink and yellow smoke pouring from the smelter. “I’ll never forget those poor, pitiful bushes hung so heavy with dust,” she recalls. “They looked like dust mops.” Under pressure from Doe Run–and with many in La Oroya supporting the company–the Peruvian Congress declined to declare the town a disaster. Still, the hearings galvanized the growing group of activists. Over the next few years, Farrell worked with local groups and nonprofits such as Earthjustice and Oxfam America to keep the pressure on. In 2004, he helped win the backing of the region’s newly appointed Catholic archbishop, Pedro Barreto. Barreto shrugged off denunciations from the Doe Run workers’ union and a death threat as he arranged the first independent study of heavy metal contamination in La Oroya.

In August 2005, scientists from St. Louis University in Missouri arrived in La Oroya lugging boxes of dust wipes, plastic baggies, syringes, and test tubes. As boys played in a dusty plaza, one team of researchers entered a small adobe home at the end of a dirt alley. They sampled water from the spigot, examined family members, and took medical histories. Forty-nine-year-old Maximina Reymundo held her one-year-old granddaughter and complained about how her eyes burned each morning. Company officials “do give support to needy towns, and that’s good,” she said, “but this pollution issue, we’re really getting tired of it.”

Other residents were less cooperative. One woman slammed her door, shouting, “No! No! I don’t want to participate. This is being done so the company will be closed.” On Calle Belaunde, a group of children threw fruit at a volunteer, shouting, “Go back to your country! You’re taking jobs here!” Angry protesters pelted the teams with rocks and eggs. “Look at our kids–they are not retarded!” one woman screamed.

The reaction was hardly surprising. For months, Doe Run had been threatening to close the smelter unless the government extended the 10-year cleanup deadline it had agreed to in 1997. It blamed unexpectedly high cleanup costs and the declining price of lead. “The markets turned against us very quickly after we came here,” Doe Run Peru’s then-president, Bruce Neil, said in an interview at his office in an upscale Lima neighborhood. “We had much, much less revenue available to do the projects.”

Though lead prices were depressed for several years, there was another reason for Doe Run Peru’s tight finances. The subsidiary had used various channels to move money from Peru to the United States, including effectively financing its own purchase by issuing an interest-free loan for $125 million to its parent company. According to a study commissioned by the Peruvian government, between 1997 and 2004 Doe Run Peru paid its corporate owner almost $100 million for salaries and commissions. Neil defended the arrangement as part of doing business, but the study concluded that Doe Run could have completed its cleanup last year if it had limited its payments to its parent company.

This past May, the Peruvian government gave Doe Run a three-year extension on its cleanup. The company now must comply with stricter environmental standards and expand its health care programs. It also has to file a report whenever it sends more than $1 million stateside. To some, these requirements don’t go far enough. The country’s constitutional court recently ordered the health ministry to protect La Oroya residents from lead poisoning–though the ruling applies only to the government, not Doe Run. Advocates have petitioned the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights for a similar decision. Local farmers have filed a $5 billion lawsuit against Doe Run and other mining companies for damaging the Mantaro River.

But even if Doe Run completes its mandatory cleanup plan, La Oroya will remain unsafe for many years to come. According to the company’s own research, many children in the town will still have blood-lead levels well above the acceptable standard. Respiratory problems will persist, and cancer risks will remain higher than U.S. standards. Residents have few ways to rid their bodies of the high levels of heavy metals confirmed by the St. Louis University study. A day-care program paid for by Doe Run has helped lower the blood-lead levels of kids with the highest readings, but by only 15 percent. More cases of severe lead poisoning have appeared in La Oroya Antigua, with one child testing at nine times the accepted standard.

Four years after Doe Run agreed to buy out its neighbors in Herculaneum, the wooden houses surrounding the smelter there have begun to come down, the vacant lots giving the streets a gap-toothed appearance. Even after the epa cleanup order, Doe Run is having trouble complying with the federal government’s air-pollution rules. Particles still fall steadily from the smelter’s stack and spill out of trucks rumbling through the town. According to the state, yards within three-quarters of a mile of the smelter that Doe Run paid to dig up and fill with clean soil a few years ago will likely be recontaminated within four years. The dust on some streets near the smelter contains as much as 25 percent lead.

Catherine Malugen, who lives with her husband and three young daughters in a tidy ranch-style house just beyond the buyout zone, no longer lets her two-year-old play outside. She says she had no idea about the contamination when her family arrived in 2000. She asked the company to buy her property, but it refused, asserting in a letter, “There are other sources of lead in the environment.”

Leslie and Jack Warden accepted Doe Run’s buyout offer of $113,000 for their home and moving expenses in 2004. They now live several miles outside town in a house looking out on the woods. Their son, now 22, has almost completed a two-year degree from a community college. He is one of more than 100 plaintiffs still waiting for their day in court against Doe Run.

Leslie Warden thinks of the children of La Oroya every day. “I was one of the lucky ones,” she says. “I was able to stand up and fight and get out. I didn’t have to worry about losing my job or anything like that. But there are still people over there who don’t have that choice.”